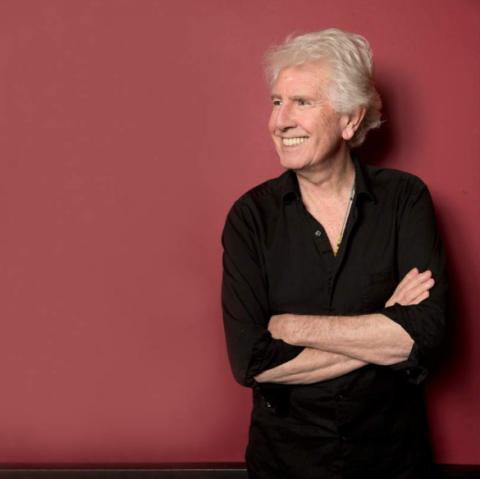

Graham Nash comes to Luther Burbank Center

Who: Graham Nash

When: 7:30 p.m., Wednesday, March 29

Where: Luther Burbank Center, 50 Mark West Springs Road, Santa Rosa

Tickets: $49 to $69

More information: lutherburbankcenter.org

Graham Nash’s life has changed greatly during the past few years. He’s ended a 38-year marriage, had a falling out with longtime bandmate David Crosby, started a new relationship and moved from Kauai to New York City.

But in some ways his life has come full circle. He’s outraged about U.S. politics and artistically committed to doing everything he can to “speak out against the madness,” as Crosby, Stills and Nash sang in the 1969 song “Long Time Gone.”

After the election of Donald Trump, Nash, who became a U.S. citizen in 1978 (he’s kept his British citizenship as well), is speaking out as vociferously as ever.

The “responsibility of every artist,” he said in a phone interview last month, is to “tell the truth as much as you can, and to reflect the times in which you live.”

The 75-year-old musician, whose harmonies with Crosby and Stephen Stills redefined rock’s sound in the late 1960s and early ’70s, believes “you really have to fight” authoritarian tendencies with art.

“I see it very differently than you do – I’m not from here. I’ve been here 50 years, but I’m not American. So I have a different perspective on this country,” Nash said.

“I believe that if America, God forbid, had been bombed like England was bombed in World War II, maybe we would be a little more cautious about going to war and preemptive military strikes.”

Nash was born in northern England in 1942, during the height of World War II. “I remember my mother pulling the blackout curtains to block out the living room light so that the enemy bombers couldn’t see the city. I remember rationing. I remember going down railroad tracks picking up bits of coal for our fire,” he said.

“Having survived World War II put me in a frame of mind that I could deal with any problem because if you can make it through World War II, the fact that your coffee is 4 degrees colder than you want it doesn’t mean anything.”

In the early ’60s, Nash co-founded the Hollies, which had several pop hits, but after a few years he became disenchanted with the band’s saccharine sound.

At a party during the summer of 1968 at Joni Mitchell’s house (Nash’s girlfriend for a time), Nash harmonized with Stills and Crosby. The trio quickly realized they had unique chemistry and formed a band.

“When we’re on it, there’s nobody like us,” Nash said. “You can’t sound like me and David and Stephen when we sing together. We wanted three voices to be one voice, one sound.”

And that’s exactly what they achieved. The debut CSN album has several songs that still sound fresh and relevant, including “Marrakesh Express,” “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes” and “Wooden Ships.”

The band gained notice for its sound, but the members carefully crafted lyrics too, for example using alliteration in “Helplessly Hoping” with such lines as “Wordlessly watching he waits by the window and wonders.”

Canadian guitarist Neil Young joined the band just before its appearance at Woodstock in August, 1969. The first album with Young, “Deja Vu” released in early 1970, included such classics as “Teach Your Children,” “Helpless” and “Our House.”

In the mid-70s, Nash wrote an album-worthy song in 20 minutes to win a bet. That song, “Just a Song Before I Go,” about missing loved ones while on tour, appeared on the album titled “CSN” in 1977. “I still have the $500,” Nash said.

When Crosby, Stills and Nash last appeared in the North Bay, at the Marin Center in 2012, they were energetic and vital, playing more than 20 songs and enthralling the adoring audience.

But it remains unclear whether CSN will reunite. A rift has developed between Nash and Crosby: Nash won’t say what happened, and last March he said there will never be another CSN album or show.

But in the Press Democrat interview in February, Nash left the door open to rapprochement.

“You say things in anger, and sometimes you say things you don’t mean,” Nash said, adding that if “David Crosby came to my apartment and said, ‘I want you to listen to four new songs,’ and he breaks my f---ing heart again, I’ll be in the studio with him.”

Nash recognizes the pettiness of the feud. “We have a lot of work to do. Look what’s going on in this country – we need to stand up and fight. It is, by far, more important than our stupid arguments.”

His most recent solo album, 2016’s “This Path Tonight” is a reflective collection. In the song, “Myself At Last,” Nash wonders, “Is my future just my past?”

The title song reflects Nash’s earnestness and desire to understand himself. “I try to question all the answers, try to answer all that’s asked. I try my best to be myself, but wonder who’s behind this mask.”

It’s a strong collection, with his guitar recalling the haunting and insistent sound of CSN’s early work.

The album is more personal than political, with Nash looking back at his long career and singing: “My dreams are only memories, but they’ve all gone by so fast.”

On “Beneath the Waves” he considers mortality, singing: “Fifty years before the mast. How long will it last, before sinking beneath the waves.”

A two-time inductee into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, for CSN and for the Hollies, Nash is also an accomplished photographer. Nash’s 1969 portrait of David Crosby is housed in the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution.

But he doesn’t see photography as that different from making music.

“If I look at the photo ‘Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico’ by Ansel Adams, I can imagine the violas in the darker clouds at the back,” he said. “I can imagine the cellos and the basses playing, I can kind of hear photographs.”

After more than half a century of making music, the ever-hopeful Nash isn’t sure how much time he has left, so he’s savoring every day.

“I’m incredibly pleased and thankful that I’ve been a musician all my life. What an incredible thing,” he said. “It’s been a strange life, and I’m loving it.”